Introduction: A Tale of Two Doctors

One of the world’s most important warning systems for a deadly new outbreak is a doctor’s or nurse’s recognition that some new disease is emerging and then sounding the alarm. It takes intelligence and courage to step up and say something like that, even in the best of circumstances.

Tom Inglesby 1, Director of the Center for Health Security at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

The world’s fastest outbreak

On February 21, 2003, a Chinese doctor named Liu Jianlun flew to Hong Kong to attend a wedding and checked into Room 911 of the Metropole Hotel. The next day, he became too ill to attend the wedding and was admitted to a hospital. Two weeks later, he was dead.

On his deathbed, Dr. Liu stated that he had recently treated sick patients in Guangdong Province, where a highly contagious respiratory illness had infected hundreds of people. The Chinese government had made brief mention of this incident to the World Health Organization (WHO) but had concluded that the likely culprit was a common bacterial infection. By the time anyone realized the severity of the disease, it was already too late to stop the outbreak.

On February 23, a man who had stayed across the hall from Dr. Liu at the Metropole traveled to Hanoi and died after infecting 80 people. On February 26, a woman checked out of the Metropole, traveled back to Toronto, and died after initiating an outbreak there. On March 1, a third guest was admitted to a hospital in Singapore, where sixteen additional cases of the illness arose within two weeks.23.

Consider that the Black Death, which killed over a third of all Europeans, took four years to travel from Constantinople to Kiev. Or that HIV took two decades to circle the globe. In contrast, this mysterious new disease had crossed the Pacific Ocean within a week of entering Hong Kong.

As health officials braced for the impact of the fastest traveling virus in human history, panic set in. Businesses were closed, sick passengers were removed from airplanes, and Chinese officials threatened to execute anyone deliberately spreading the disease. In the process, the mysterious new illness earned a name: severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS.

Tracing the source of the outbreak

SARS was deadly, killing close to 10% of those who became sick.4 But it also struggled to spread within the human population, and it was contained in July 2003 after accumulating fewer than 10,000 confirmed symptomatic cases worldwide.

In 2017, researchers published the results of sampling horseshoe bats for five years in a cave in Yunnan province. They found that these bats harbored coronaviruses with remarkable genetic similarity to the virus causing SARS. Yet their work has become infamous because they identified additional coronaviruses in the bats that were capable of entering human cells. Their words are now chilling:5

We have also revealed that various [viruses] … are still circulating among bats in this region. Thus, the risk of spillover into people and emergence of a disease similar to SARS is possible. This is particularly important given that the nearest village to the bat cave we surveyed is only 1.1 km away, which indicates a potential risk of exposure to bats for the local residents. Thus, we propose that monitoring of SARSr-CoV evolution at this and other sites should continue, as well as examination of human behavioral risk for infection and serological surveys of people, to determine if spillover is already occurring at these sites and to design intervention strategies to avoid future disease emergence.

A new threat emerges

On December 30, 2019, a Chinese ophthalmologist named Li Wenliang sent a WeChat message to fellow doctors at Wuhan Central Hospital, warning them that he had seen several patients with symptoms resembling SARS 1. He urged his colleagues to wear protective clothing and masks to shield them from this new threat.

The next day, a screenshot of his post was leaked online, and local police summoned Dr. Li and forced him to sign a statement that he had “severely disturbed public order”. He then returned to work, treating patients in the same Wuhan hospital.

Meanwhile, WHO received reports of multiple pneumonia cases from the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission and activated a support team to assess the new disease. WHO declared on January 14 that local authorities had seen “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus”. But once again, it was already too late.

Throughout January, the virus silently raged through China as Lunar New Year celebrations took place within the country, and it spread to both South Korea and the United States. By the end of the month, the disease was in 19 countries, becoming a pandemic and earning a name in the process: coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

As for Dr. Li? Despite warning against the risk of the new virus, he contracted COVID-19 from one of his patients on January 8. He continued working until he was forced to be admitted to the hospital on January 31. Within a week, he was dead, one of the first of millions of COVID-19 casualties.

The sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein

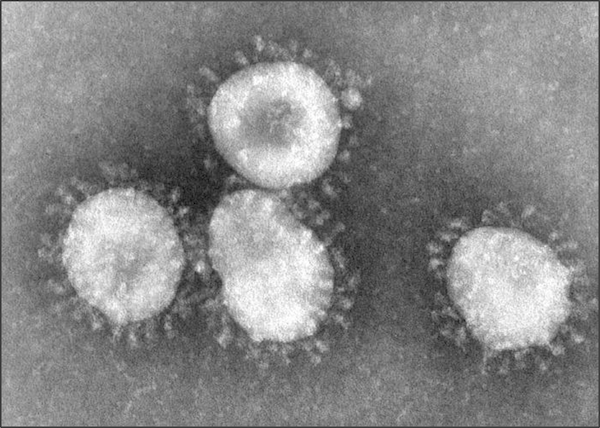

The viruses causing the two outbreaks, SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are both coronaviruses, which means that their outer membranes are covered in a layer of spike proteins that cause them to look like the sun’s corona during an eclipse (see figure below).

Coronaviruses as seen under a microscope. The fuzzy blobs on the cell surface are spike proteins, which the virus uses to gain entry to host cells. Figure courtesy F. Murphy and S. Whitfield, CDC6.

Coronaviruses as seen under a microscope. The fuzzy blobs on the cell surface are spike proteins, which the virus uses to gain entry to host cells. Figure courtesy F. Murphy and S. Whitfield, CDC6.

When viewed under a microscope, the two viruses look identical, and they use the same mechanism to infect human cells, when the spike protein on the virus surface bonds to the ACE2 enzyme on a human cell’s membrane.78 So why did SARS fizzle, but SARS-CoV-2, a disease that is on average less harmful910 and less deadly to individuals who contract it, transform into a pandemic? The most likely explanation for the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to spread across far more countries and remain a public health threat even in the face of lockdowns is that it spreads more easily; that is, it is more infectious. Is there a molecular basis of this increased infectiousness?

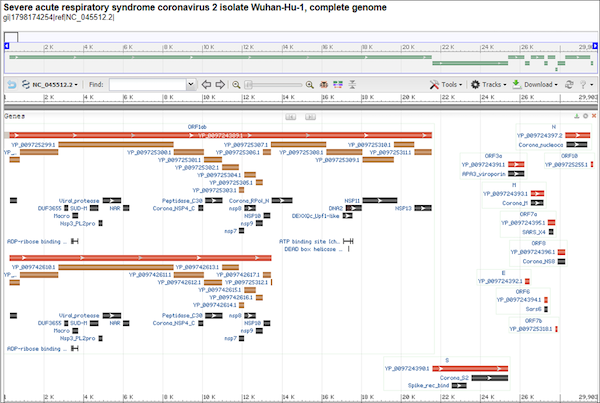

In this module, we will place ourselves in the shoes of early SARS-CoV-2 researchers studying the new virus in early 2020. The virus’s genome, consisting of nearly 30,000 nucleotides, was published on January 101112, and an annotation of this genome identifying the location of the virus’s genes is shown in the figure below. Upon sequence comparison, SARS-CoV-2 was found to be related to several coronaviruses isolated from bats and distantly related to SARS-CoV.

An annotated genome of SARS-CoV-2, with rectangles showing the location of areas encoding RNA or protein. The spike protein, found at the bottom of this image, is labeled “S” and begins at nucleotide position 21,563. Accessed from GenBank: https://go.usa.gov/xfzMM.

An annotated genome of SARS-CoV-2, with rectangles showing the location of areas encoding RNA or protein. The spike protein, found at the bottom of this image, is labeled “S” and begins at nucleotide position 21,563. Accessed from GenBank: https://go.usa.gov/xfzMM.

Recall from our discussion of transcription factors that by the central dogma of molecular biology, DNA is transcribed into RNA, which is then translated into protein. According to the genetic code, triplets of RNA nucleotides called codons are converted into single amino acids. The resulting chain of amino acids is called a polypeptide.

Note: Coronaviruses are RNA viruses, which means that they do not have DNA and their genome is encoded as a single strand of RNA. As a result, they bypass the DNA to RNA transcription process.

The gene encoding the spike protein starts at nucleotide position 21,563 of the SARS-CoV-2 genome, and the corresponding translated polypeptide chain is shown below. Each of the 20 standard amino acids is represented by a letter taken from the Latin alphabet (all letters except for “B”, “J”, “O”, “U”, “X”, and “Z” are used). As you examine the string of letters in this figure, consider how global mayhem can ultimately be caused by something so tiny.

>YP_009724390.1 S [organism=Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2] [GeneID=43740568]

MFVFLVLLPLVSSQCVNLTTRTQLPPAYTNSFTRGVYYPDKVFRSSVLHSTQDLFLPFFSNVTWFHAIHV

SGTNGTKRFDNPVLPFNDGVYFASTEKSNIIRGWIFGTTLDSKTQSLLIVNNATNVVIKVCEFQFCNDPF

LGVYYHKNNKSWMESEFRVYSSANNCTFEYVSQPFLMDLEGKQGNFKNLREFVFKNIDGYFKIYSKHTPI

NLVRDLPQGFSALEPLVDLPIGINITRFQTLLALHRSYLTPGDSSSGWTAGAAAYYVGYLQPRTFLLKYN

ENGTITDAVDCALDPLSETKCTLKSFTVEKGIYQTSNFRVQPTESIVRFPNITNLCPFGEVFNATRFASV

YAWNRKRISNCVADYSVLYNSASFSTFKCYGVSPTKLNDLCFTNVYADSFVIRGDEVRQIAPGQTGKIAD

YNYKLPDDFTGCVIAWNSNNLDSKVGGNYNYLYRLFRKSNLKPFERDISTEIYQAGSTPCNGVEGFNCYF

PLQSYGFQPTNGVGYQPYRVVVLSFELLHAPATVCGPKKSTNLVKNKCVNFNFNGLTGTGVLTESNKKFL

PFQQFGRDIADTTDAVRDPQTLEILDITPCSFGGVSVITPGTNTSNQVAVLYQDVNCTEVPVAIHADQLT

PTWRVYSTGSNVFQTRAGCLIGAEHVNNSYECDIPIGAGICASYQTQTNSPRRARSVASQSIIAYTMSLG

AENSVAYSNNSIAIPTNFTISVTTEILPVSMTKTSVDCTMYICGDSTECSNLLLQYGSFCTQLNRALTGI

AVEQDKNTQEVFAQVKQIYKTPPIKDFGGFNFSQILPDPSKPSKRSFIEDLLFNKVTLADAGFIKQYGDC

LGDIAARDLICAQKFNGLTVLPPLLTDEMIAQYTSALLAGTITSGWTFGAGAALQIPFAMQMAYRFNGIG

VTQNVLYENQKLIANQFNSAIGKIQDSLSSTASALGKLQDVVNQNAQALNTLVKQLSSNFGAISSVLNDI

LSRLDKVEAEVQIDRLITGRLQSLQTYVTQQLIRAAEIRASANLAATKMSECVLGQSKRVDFCGKGYHLM

SFPQSAPHGVVFLHVTYVPAQEKNFTTAPAICHDGKAHFPREGVFVSNGTHWFVTQRNFYEPQIITTDNT

FVSGNCDVVIGIVNNTVYDPLQPELDSFKEELDKYFKNHTSPDVDLGDISGINASVVNIQKEIDRLNEVA

KNLNESLIDLQELGKYEQYIKWPWYIWLGFIAGLIAIVMVTIMLCCMTSCCSCLKGCCSCGSCCKFDEDD

SEPVLKGVKLHYT

Nature’s magic protein folding algorithm

After the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein polypeptide chain is formed, it will “fold” into a three-dimensional shape. This folding process occurs spontaneously for all proteins and without any outside influence, and the same polypeptide chain will almost always fold into the same 3-D structure in a manner of microseconds. Nature must be applying some “magic algorithm” to quickly produce the folded structure of a protein from its sequence of amino acids.

Predicting the folded structure of a polypeptide is called the protein structure prediction, a problem that is simple to state but difficult to solve. In fact, protein structure prediction has been an active area of biological research for several decades.

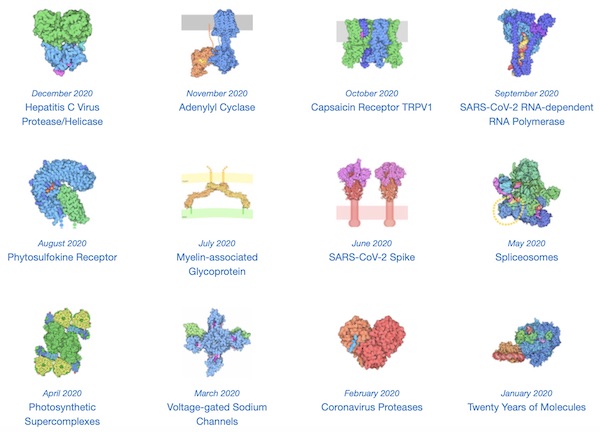

Why do we care about protein structure? Knowing a protein’s structure is essential to determining its function and how it interacts with other proteins or molecules in its environment. After all, we still do not know the function of a few thousand human genes, and Figure 1.4 shows the huge variety of protein shapes in the 2020 “proteins of the month” named by the Protein Data Bank (PDB). (Note that the June 2020 winner is the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.)

Each “molecule of the month” in 2020 named by the PDB. These proteins have widely varying shapes and accomplish a wide variety of cellular tasks. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein was the molecule of the month in June. Image courtesy: David Goodsell.

Each “molecule of the month” in 2020 named by the PDB. These proteins have widely varying shapes and accomplish a wide variety of cellular tasks. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein was the molecule of the month in June. Image courtesy: David Goodsell.

For a more visual example of how protein structure affects protein function, consider the following video of a ribosome (which is a complex of RNA and proteins) translating a messenger RNA into protein. For translation to succeed, the ribosome needs to have a very precise shape, including a “slot” into which the messenger RNA strand can fit.

Another central problem in protein structural research is devoted to understanding protein interactions. For example, a disease may be caused by a faulty protein, in which case researchers want to find a drug that binds to the protein and causes some change of interest in that protein, such as inhibiting its behavior.

In this module, we will consider two questions. First, can we reverse engineer nature’s magic algorithm and determine the spike protein’s shape from its sequence of amino acids in the figure above? Second, once we know this molecular structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, how does its structure and function differ from the same protein in SARS-CoV?

These two questions are both significant, and so we will split our work on them over two parts. If you are already familiar with protein structure prediction, then you may want to skip ahead to the second part of the module, in which we discuss differences between the spike proteins of the two viruses.

Continue to part 1: structure prediction

Jump to part 2: spike protein comparisons

-

Green, A. (2020, February 18). Li Wenliang. The Lancet, 395(10225), P682. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30382-2 ↩ ↩2

-

Hung L. S. 2003. The SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: what lessons have we learned?. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96(8), 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.96.8.374 ↩

-

Update 95 - SARS: Chronology of a serial killer. (2015, July 24). Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://www.who.int/csr/don/2003_07_04/en/ ↩

-

CDC SARS Response Timeline. 2013, April 26. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/about/history/sars/timeline.htm ↩

-

Hu, B., Zeng, L., Yang, X., Ge, X., Zhang, W., Li, B., Xie, J., Shen, X., Zhang, Y., Wang, N., Luo, D., Zheng, X., Wang, M., Daszak, P., Wang, L., Cui, J., Shi, Z. 2017. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLOS Pathogens, 13(11). doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698 ↩

-

Murphy, F., Whitfield, S. 1975. ID#: 10270. Public Health Image Library, CDC. https://phil.cdc.gov/Details.aspx?pid=10270 ↩

-

Shang, J., Ye G., Shi, K., Wan, Y., Luo, C., Aihara, H., Geng, Q., Auerbach, A., Li, F. 2020. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 581, 221-224. ↩

-

Li, F., Li, W., Farzan, M., Harrison, S. C. 2005. Structure of SARS Coronavirus Spike Receptor-Binding Domain Complexed with Receptor. Science 309, 1864-1868. ↩

-

Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19). (2020, April 17). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses ↩

-

Paules C.I., Marston H.D., Fauci A.S. 2020. Coronavirus Infections—More Than Just the Common Cold. JAMA. 323(8):707–708. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.0757 ↩

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, complete genome. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MN908947 ↩

-

Annotated Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, complete genome. https://go.usa.gov/xfzMM ↩