Laboratory methods for determining protein structure

Although we would like to infer nature’s magic algorithm for inferring protein structure from amino acid sequence, biochemists can determine the structure of a protein experimentally. We will introduce two popular and sophisticated laboratory methods for accurately determining protein structure. We appeal to high-quality videos explaining them if you are interested.

In X-ray crystallography, researchers crystallize many copies of a protein and then shine an intense beam of X-rays at the crystal. The light hitting the protein is diffracted, creating patterns from which the position of every atom in the protein can be inferred. If you are interested in learning more about X-ray crystallography, check out the following excellent two-part video series from The Royal Institution.

X-ray crystallography is over a century old and has been the de facto approach for protein structure determination for decades. Yet a newer method is now rapidly replacing X-ray crystallography.

In cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), researchers preserve thousands of copies of a protein in non-crystalline ice and then examine these copies with an electron microscope. Check out the following YouTube video from the University of California San Francisco for a detailed discussion of cryo-EM.

Unfortunately, laboratory approaches for structure determination are expensive and cannot be used on all proteins. An X-ray crystallography experiment for a single protein costs upward of $2,000, and building an electron microscope can cost millions. When applying X-ray crystallography, crystallizing a protein is a challenging task, and each copy of the protein must line up in the same way, which does not work for very flexible proteins. And to study bacterial proteins, we need to culture the bacteria in the lab, but microbiologists have estimated that fewer than 2% of bacteria can be cultured with current approaches.1

Protein structures that have been determined experimentally are typically stored in the PDB, which contains over 160,000 protein structures. This number may seem large, but a recent study estimated that the 20,000 human genes translate into between 620,000 and 6.13 million protein isoforms (i.e., protein variants with slightly different structures).2 If we hope to catalog the proteins of all living things, then our work on structure determination is just beginning.

Protein sequence and structure do not correlate well

The prediction of protein structure from amino acid sequence is challenging because this prediction is fine-tuned with respect to some mutations but robust with respect to others. On the one hand, small perturbations in a protein’s sequence can drastically change the protein’s shape and even render it useless. On the other hand, different amino acids can have similar chemical properties, and so some sequence mutations will hardly change the structure of the protein. As a result, two very different amino acid sequences can fold into proteins having similar structure and comparable function.

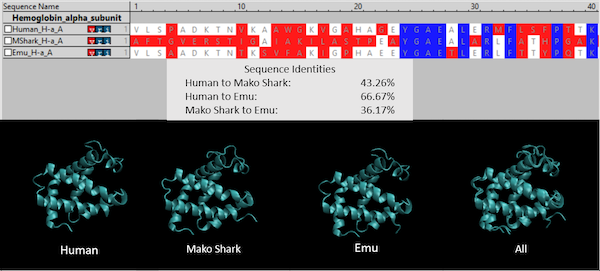

Continuing with our hemoglobin example, the following figure compares the sequences and structures of hemoglobin subunit alpha taken from three species: humans (PDB: 1si4), shortfin mako sharks (PDB: 3mkb), and emus (PDB: 3wtg). Hemoglobin is the oxygen-transport protein in the blood, consisting of two alpha “subunit” proteins and two beta subunit proteins that combine into a protein complex; because hemoglobin is well-studied and much shorter than the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (the alpha and beta subunits are only 140 and 147 amino acids long, respectively), we will use it as an example throughout this module. The alpha subunits for the three species are markedly different in terms of amino acid sequence, and yet their 3-D structures are essentially identical.

(Top) An amino acid sequence comparison of the first 40 (out of 140) amino acids of hemoglobin subunit alpha for three species: human, shortfin mako shark, and emu. A column is colored blue if all three species have the same amino acid, white if two species have the same amino acid, and red if all amino acids are different. Sequence identity calculates the number of positions in two amino acid sequences that share the same amino acid. (Bottom) Side by side comparisons of the 3-D structures of the three proteins. The final figure on the right superimposes the first three structures to highlight that they are virtually identical.

(Top) An amino acid sequence comparison of the first 40 (out of 140) amino acids of hemoglobin subunit alpha for three species: human, shortfin mako shark, and emu. A column is colored blue if all three species have the same amino acid, white if two species have the same amino acid, and red if all amino acids are different. Sequence identity calculates the number of positions in two amino acid sequences that share the same amino acid. (Bottom) Side by side comparisons of the 3-D structures of the three proteins. The final figure on the right superimposes the first three structures to highlight that they are virtually identical.

Flexible polypeptide chains can fold into many possible structures

Another reason why protein structure prediction is so difficult is because a polypeptide is very flexible, with the ability to rotate in multiple ways at each amino acid, which means that the polypeptide can fold into a staggering number of different shapes. This polypeptide flexibility owes to the molecular structure of amino acids.

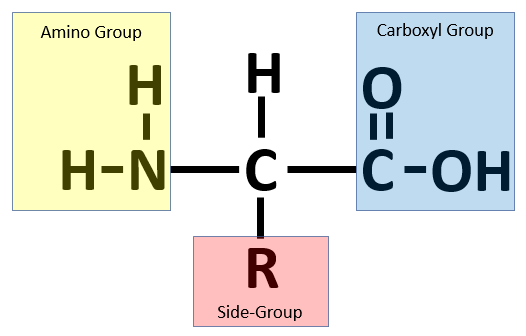

As shown in the figure below, an amino acid comprises four parts. In the center, a carbon atom (called the alpha carbon) is connected to four different molecules: a hydrogen atom (H), a carboxyl group (–COOH), an amino group (-NH2), and a side chain (denoted “R” and often called an R group). The side chain is a molecule that differs between different amino acids and ranges in mass from a single hydrogen atom (glycine) up to -C8H7N (tryptophan).

An amino acid consists of a central alpha carbon attached to a hydrogen atom, a side group, a carboxyl group, and an amino group.

An amino acid consists of a central alpha carbon attached to a hydrogen atom, a side group, a carboxyl group, and an amino group.

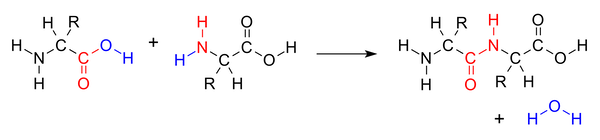

To form a polypeptide chain, consecutive amino acids are linked together during a condensation reaction in which the amino group of one amino acid is joined to the carboxyl group of another, while a water molecule (H2O) is expelled (see figure below).

A condensation reaction joins two amino acids into a “dipeptide” by joining the amino group of one amino acid to the carboxyl group of the other, with a water molecule expelled. Source: https://bit.ly/3q0Ph8V.

A condensation reaction joins two amino acids into a “dipeptide” by joining the amino group of one amino acid to the carboxyl group of the other, with a water molecule expelled. Source: https://bit.ly/3q0Ph8V.

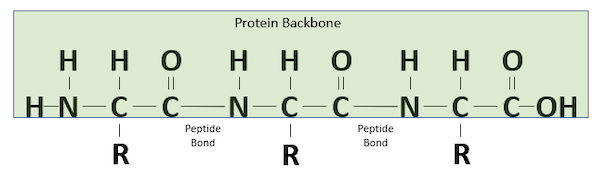

The resulting bond that is produced between the carbon atom of one amino acid’s carboxyl group and the nitrogen atom of the next amino acid’s amino group, called a peptide bond, is very strong. The peptide has very little rotation around this bond, which is almost always locked at 180°. As peptide bonds are formed between adjacent amino acids, the polypeptide chain takes shape, as shown in the figure below.

A polypeptide chain formed of three amino acids.

A polypeptide chain formed of three amino acids.

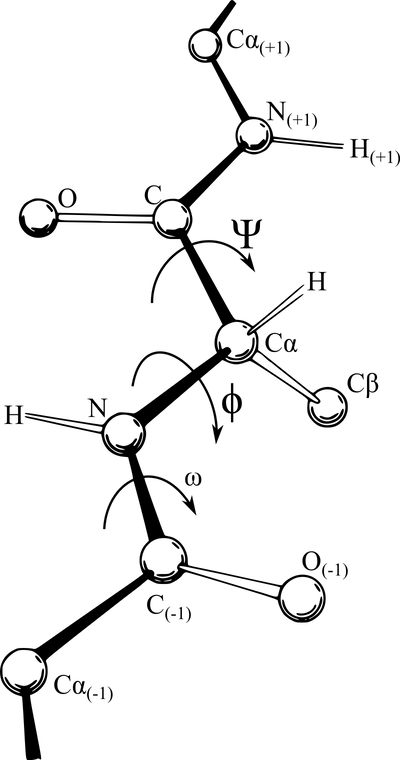

However, the bonds within an amino acid, joining the alpha carbon to its carboxyl group and amino group, are not as rigid, and the polypeptide is free to rotate around these two bonds. This rotation produces two angles of interest, called the phi angle (φ) and psi angle (ψ) (see figure below), which are formed at the alpha carbon’s connections to its amino group and carboxyl group, respectively.

A polypeptide chain of multiple amino acids with the torsion angles φ and ψ indicated. The angle ω indicates the angle of the peptide bond, which is typically 180°. Image courtesy: Adam Rędzikowski.

A polypeptide chain of multiple amino acids with the torsion angles φ and ψ indicated. The angle ω indicates the angle of the peptide bond, which is typically 180°. Image courtesy: Adam Rędzikowski.

Below is an excellent video from Jacob Elmer illustrating how changing φ and ψ at a single amino acid can drastically reorient a protein’s shape.

A good analogy for polypeptide flexibility is the “Rubik’s Twist” puzzle, shown in the video below, which consists of a linear chain of flexible blocks that can form many different shapes.

A polypeptide with n amino acids has n - 1 peptide bonds, meaning that its shape is influenced by n - 1 phi angles and n - 1 psi angles. If each bond angle has k possible values, then the polypeptide has k2n-2 total possible conformations. If k is equal to 3 and n is equal to only 100 (representing a short polypeptide), then the number of potential protein structures is more than the number of atoms in the universe! The ability of the magic algorithm to reliably find a single conformation despite such an enormous number of potential shapes is called Levinthal’s paradox.3

Although protein structure prediction is difficult, it is not impossible; the magic algorithm is not, after all, magic. But before discussing how we can solve this problem, we will need to learn a few more biochemical details and be more precise about two things. First, we should specify what we mean by the “structure” of a protein. Second, although we know that a polypeptide always folds into the same final three-dimensional shape, we have not said anything about why a protein folds in a certain way. We will therefore need a better understanding of how the physicochemical properties of amino acids influence a protein’s final structure.

-

Wade W. 2002. Unculturable bacteria–the uncharacterized organisms that cause oral infections. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 95(2), 81–83. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.95.2.81 ↩

-

Ponomarenko, E. A., Poverennaya, E. V., Ilgisonis, E. V., Pyatnitskiy, M. A., Kopylov, A. T., Zgoda, V. G., Lisitsa, A. V., & Archakov, A. I. 2016. The Size of the Human Proteome: The Width and Depth. International journal of analytical chemistry, 2016, 7436849. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7436849 ↩

-

Levinthal, C. 1969. How to Fold Graciously. Mossbaur Spectroscopy in Biological Systems, Proceedings of a meeting held at Allerton House, Monticello, Illinois. eds. Debrunner, P., Tsibris, J.C.M., Munck, E. University of Illinois Press Pages 22-24. ↩

Leanpub

Leanpub