Introduction: Segmenting and counting white blood cells

Your doctor sometimes counts your blood cells to ensure that they are within healthy ranges as part of a complete blood count. These cells comprise red blood cells (RBCs), which transport oxygen via the hemoglobin protein, and white blood cells (WBCs), which help identify and attack foreign cells as part of your immune system.

The classic device used for counting blood cells is the hemocytometer. As illustrated in the video below, a technician filters a small amount of blood onto a gridded slide and then counts the number of cells of each type in the squares on the grid. As a result, the technician can estimate the number of each type of cell per volume of blood.

STOP: How could the volume of a blood sample influence the estimate of blood cell count?

You would not be wrong to think that the hemocytometer seems old-fashioned, as it was invented by Louis-Charles Malassez 150 years ago. To reduce the human error inherent in using this device, can we train a computer to count blood cells for us?

In this module, we will focus our work on WBCs, which divide into families based on their structure and function, with some diseases causing an abnormally low or high count of cells in a specific family. We therefore have two aims. First, can we excise, or segment, WBCs from cellular images? Second, can we devise an algorithm to classify WBCs by family?

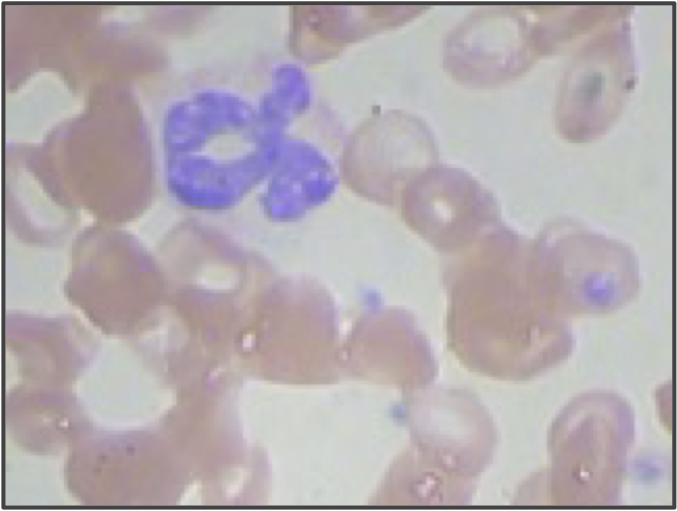

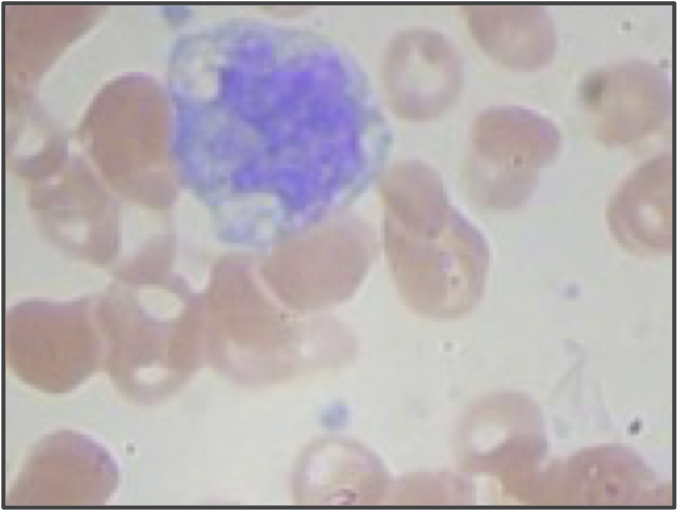

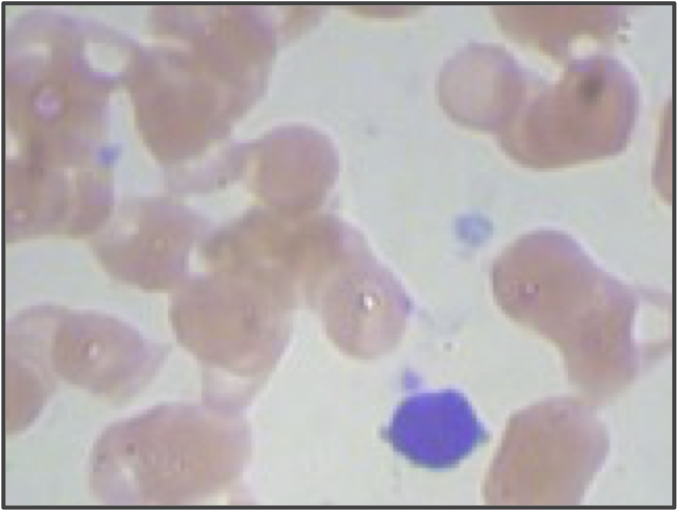

We will work with a publicly available dataset containing blood cell images that depict both RBCs and WBCs, as shown in the figure below. The cells have been stained with a red-orange dye that bonds to hemoglobin and a blue dye that bonds to DNA and RNA. RBCs lack a nucleus and will only absorb the red-orange dye, whereas WBCs have a nucleus but lack hemoglobin and will only absorb the blue dye.

The figure below also illustrates the three main families of WBCs: granulocytes, monocytes, and lymphocytes. Granulocytes have a multilobular nucleus, which consists of several “lobes” that are linked by thin strands of nuclear material. Monocyte and lymphocyte nuclei only have a single lobe, but monocyte nuclei have a more irregular shape, whereas lymphocyte nuclei are more rounded and take up a greater fraction of the cell’s volume.

When you look at the cells in the figure above, you may think that our work will be easy. Segmenting WBC nuclei only requires identifying the large purplish regions, and classifying them is just a matter of categorizing them according to the differences in nuclear shape that we described above. Yet even after decades of research into computer vision, researchers struggle to attain the precision of the human eye, a biological apparatus that is the result of billions of years of evolution.