The four levels of protein structure

Protein structure is a broad term that encapsulates four different levels of description. A protein’s primary structure refers to the amino acid sequence of the polypeptide chain. The primary structure of human hemoglobin subunit alpha can be downloaded here, and the primary structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, which we showed earlier, can be downloaded here.

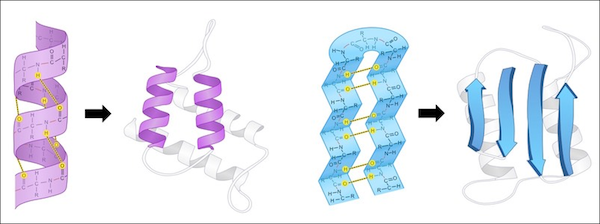

A protein’s secondary structure describes its highly regular, repeating intermediate substructures that form before the overall protein folding process completes. The two most common such substructures, shown in the figure below, are alpha helices and beta sheets. Alpha helices occur when nearby amino acids wrap around to form a tube structure; beta sheets occur when nearby amino acids line up side-by-side.

The general shape of alpha helices (left) and beta sheets (right), the two most common protein secondary structures. Source: Cornell, B. (n.d.). https://ib.bioninja.com.au/higher-level/topic-7-nucleic-acids/73-translation/protein-structure.html

The general shape of alpha helices (left) and beta sheets (right), the two most common protein secondary structures. Source: Cornell, B. (n.d.). https://ib.bioninja.com.au/higher-level/topic-7-nucleic-acids/73-translation/protein-structure.html

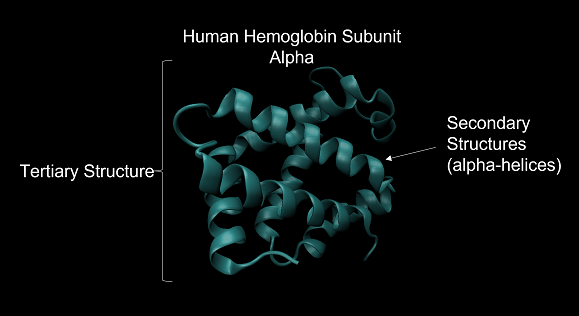

A protein’s tertiary structure describes its final 3D shape after the polypeptide chain has folded and is chemically stable. Throughout this module, when discussing the “shape” or “structure” of a protein, we are almost exclusively referring to its tertiary structure. The figure below shows the tertiary structure of human hemoglobin subunit alpha. For the sake of simplicity, this figure does not show the position of every atom in the protein but rather represents the protein shape as a composition of secondary structures.

The tertiary structure of human hemoglobin subunit alpha. Within the structure are multiple alpha helix secondary structures. Source: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1SI4.

The tertiary structure of human hemoglobin subunit alpha. Within the structure are multiple alpha helix secondary structures. Source: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1SI4.

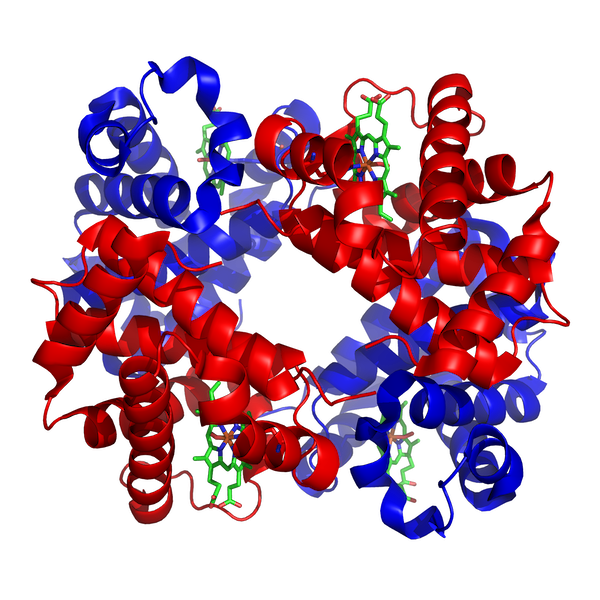

Finally, some proteins have a quaternary structure, which describes the protein’s interaction with other copies of itself to form a single functional unit, or a multimer. Many proteins do not have a quaternary structure and function as an independent monomer. The figure below shows the quaternary structure of hemoglobin, which is a multimer consisting of two alpha subunits and two beta subunits.

The quaternary structure of human hemoglobin, which consists of two alpha subunits (shown in red) and two beta subunits (shown in blue). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1GZX_Haemoglobin.png.

The quaternary structure of human hemoglobin, which consists of two alpha subunits (shown in red) and two beta subunits (shown in blue). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1GZX_Haemoglobin.png.

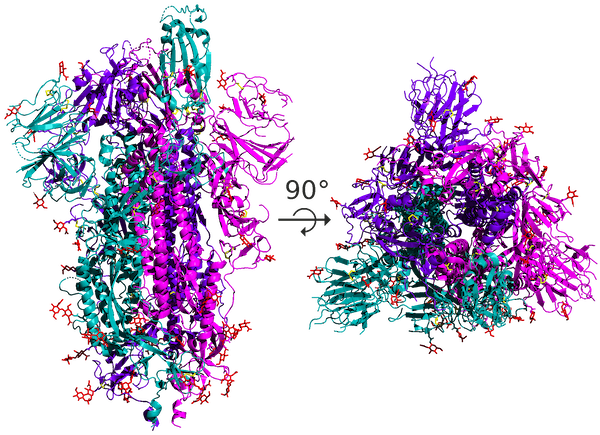

As for coronaviruses, the spike protein is a homotrimer, meaning that it is formed of three essentially identical units called chains, each one translated from the corresponding region of the coronavirus’s genome; these chains are colored differently in the figure below. In this module, when discussing the structure of the spike protein, we often are referring to the structure of a single chain.

A side and top view of the quaternary structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein homotrimer, with its three chains highlighted using different colors.

A side and top view of the quaternary structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein homotrimer, with its three chains highlighted using different colors.

The structural units making up proteins are often hierarchical, and the spike protein is no exception. Each spike protein chain is a dimer, consisting of two subunits called S1 and S2. Each of these subunits further divides into protein domains, distinct structural units within the protein that fold independently and are typically responsible for a specific interaction or function. For example, the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein has a receptor binding domain (RBD) located on the S1 subunit of the spike protein that is responsible for interacting with the human ACE2 enzyme; the rest of the protein does not come into contact with ACE2. We will say more about the RBD soon.

Proteins seek the lowest energy conformation

Now that we know a bit more about how protein structure is defined, we will discuss why proteins fold in the same way every time. In other words, what are the factors driving the magic algorithm?

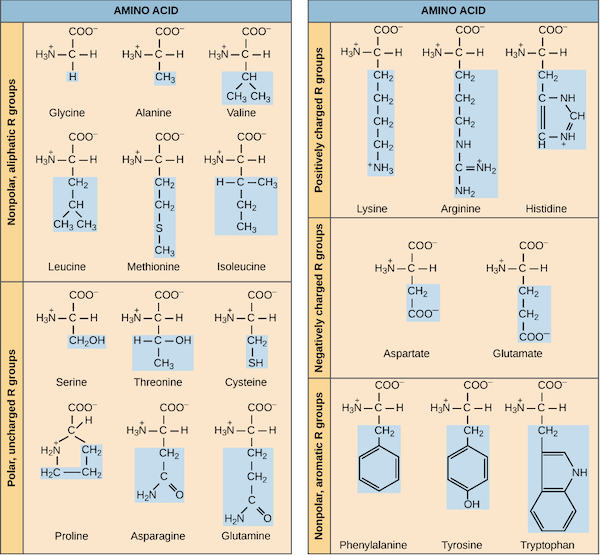

Amino acids’ side chain variety causes them to have different chemical properties, which can lead to some protein conformations being more chemically “preferable” than others. For example, the table below groups the twenty amino acids commonly occurring in proteins according to their chemical properties. Nine of these amino acids are hydrophobic (also called nonpolar), meaning that their side chains are repelled by water, and so we tend to find these amino acids tucked away on the interior of the protein.

A chart of the twenty amino acid grouped by chemical properties. The side chain of each amino acid is highlighted in blue. Image courtesy: OpenStax Biology.

A chart of the twenty amino acid grouped by chemical properties. The side chain of each amino acid is highlighted in blue. Image courtesy: OpenStax Biology.

We can therefore view protein folding as finding the tertiary structure that is the most stable given a polypeptide’s primary structure. A central theme of the previous module on bacterial chemotaxis was that a system of chemical reactions moves toward equilibrium. The same principle is true of protein folding; when a protein folds into its final structure, it reaches a conformation that is as chemically stable as possible.

To be more precise, the potential energy (sometimes called free energy) of a molecule is the energy stored within an object due to its position, state, and arrangement. In molecular mechanics, the potential energy is made up of the sum of bonded energy and non-bonded energy.

As the protein bends and twists into a stable conformation, bonded energy derives from the protein’s covalent bonds, as well as the bond angles between adjacent amino acids, and the torsion angles that we introduced in the previous lesson.

Non-bonded energy comprises electrostatic interactions and van der Waals interactions. Electrostatic interactions refer to the attraction and repulsion force from the electric charge between pairs of charged amino acids. Two of the twenty standard amino acids (arginine and lysine) are positively charged, and two (aspartic acid and glutamic acid) are negatively charged. Two nearby amino acids of opposite charge may interact to form a salt bridge. Conformations that contain salt bridges and keep apart similarly charged amino acids will therefore have a lower free energy component contributed by electrostatic interactions.

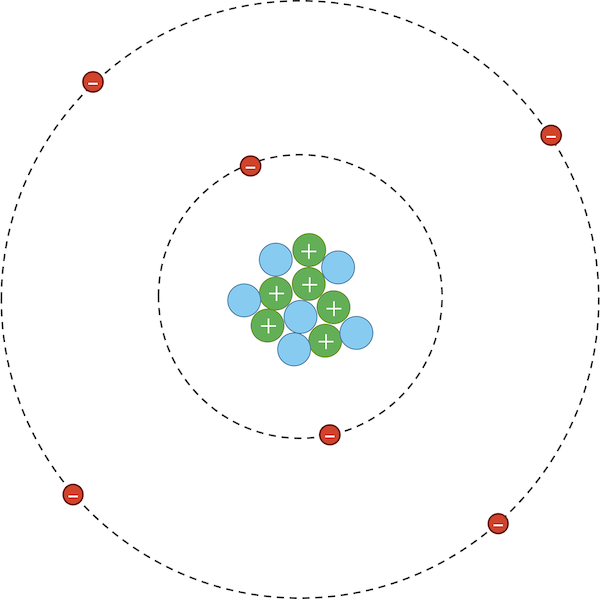

As for van der Waals interactions, atoms are dynamic systems, with electrons constantly buzzing around the nucleus, as shown in the figure below.

A carbon-12 atom showing six positively charged protons (green), six neutrally charged neutrons (blue), and six negatively charged electrons (red). Under typical circumstances, the electrons will most likely be distributed uniformly around the nucleus.

A carbon-12 atom showing six positively charged protons (green), six neutrally charged neutrons (blue), and six negatively charged electrons (red). Under typical circumstances, the electrons will most likely be distributed uniformly around the nucleus.

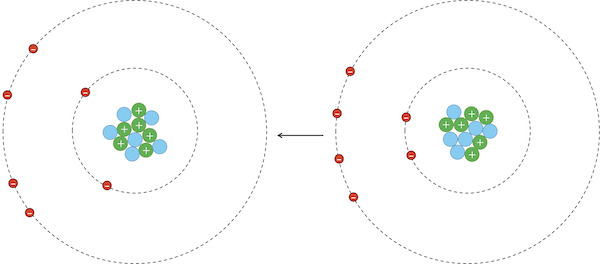

However, due to random chance, the negatively charged electrons in an atom could momentarily be unevenly distributed on one side of the nucleus. This uneven distribution will cause the atom to have a temporary negative charge on the side with the excess electrons and a temporary positive charge on the opposite side. As a result of this charge, one side of the atom may attract only the oppositely charged components of another atom, creating an induced dipole in that atom in turn as shown in the figure below. Van der Waals forces refer to the attraction and repulsion between atoms because of induced dipoles.

Due to random chance, the electrons in the atom on the left have clustered on the left side of the atom, creating a net negative charge on this side of the atom, and therefore a net positive charge on the right side of the atom. This polarity induces a dipole in the atom on the right, whose electrons are attracted because of van der Waals forces.

Due to random chance, the electrons in the atom on the left have clustered on the left side of the atom, creating a net negative charge on this side of the atom, and therefore a net positive charge on the right side of the atom. This polarity induces a dipole in the atom on the right, whose electrons are attracted because of van der Waals forces.

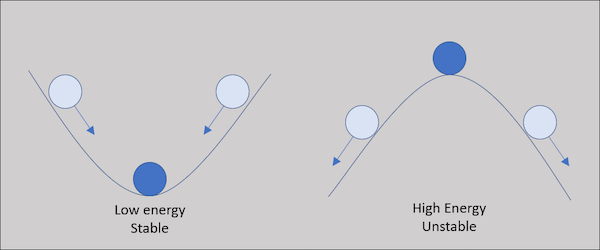

As the protein folds, it seeks a conformation of lowest total potential energy based on the combination of all the above-mentioned forces. For an analogy, imagine a ball on a slope, as shown in the following figure. The ball will move down the slope unless it is pushed uphill by some outside force, making it unlikely that the ball will wind up at the top of a hill. We will keep this analogy in mind as we return to the problem of protein structure prediction.

A ball on a hill offers an analogy for a protein folding into the lowest energy structure. As the ball is more likely to move down into a valley, a protein is more likely to fold into a more stable, lower energy conformation.

A ball on a hill offers an analogy for a protein folding into the lowest energy structure. As the ball is more likely to move down into a valley, a protein is more likely to fold into a more stable, lower energy conformation.

Leanpub

Leanpub