Modeling ab initio structure prediction as an exploration problem

Predicting a protein’s structure using only its amino acid sequence is called ab initio structure prediction (ab initio means “from the beginning” in Latin). Although many different algorithms have been developed for ab initio protein structure through the years, these algorithms all find themselves solving a similar problem.

Biochemical research has contributed to the development of scoring functions called force fields that use the physicochemical properties of amino acids introduced in the previous lesson to compute the potential energy of a candidate protein shape. For a given choice of force field, we can think of ab initio structure prediction as solving the following problem: given a primary structure of a polypeptide, find its tertiary structure having minimum energy. This problem exemplifies an optimization problem, in which we are seeking an object maximizing or minimizing some function subject to constraints.

The formulation of protein structure prediction as an optimization problem may not strike you as similar to anything that we have done before in this course. However, consider once more a bacterium exploring an environment for food. Every point in the bacterium’s “search space” is characterized by a concentration of attractant, and the bacterium’s goal is to reach the point of maximum attractant concentration.

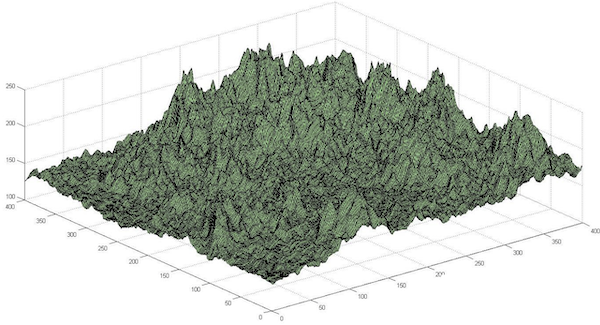

In the case of structure prediction, our search space is the collection of all possible conformations of a given protein, and each point in this search space represents a single conformation with an associated potential energy. Just as we imagined a ball rolling down a hill to find lower energy, we can now imagine exploring the search space of all conformations of a polypeptide to find the conformation having lowest energy. The general problem of exploring a search space to find a point minimizing some function is illustrated in the figure below, in which the height of each point represents the value of the function at that point, and our goal is to find the lowest point in the space.

Optimization problems can be thought of as exploring a landscape, in which the height of a point is the value of the function that we wish to optimize. Finding the highest or lowest point in this landscape corresponds to maximizing or minimizing the function over the search space. Image courtesy: David Beamish.

Optimization problems can be thought of as exploring a landscape, in which the height of a point is the value of the function that we wish to optimize. Finding the highest or lowest point in this landscape corresponds to maximizing or minimizing the function over the search space. Image courtesy: David Beamish.

A local search algorithm for ab initio structure prediction

Now that we have conceptualized the protein structure prediction problem as exploring a search space, we will develop an algorithm to explore this space. Our idea is to use an approach similar to E. coli’s clever exploration algorithm from a previous module: over a sequence of steps, we will consult a collection of nearby points in the space, and then move in the “direction” in which the energy function decreases the most. This approach belongs to a broad category of optimization algorithms called local search algorithms.

Adapting a local search algorithm to protein structure prediction requires us to develop a notion of what it means to consider the points “nearby” a given conformation in a protein search space. Many ab initio algorithms start at an arbitrary initial conformation and then make a variety of minor modifications to that structure (i.e., nearby points in the space), updating the current conformation to the modification that produces the greatest decrease in free energy. These algorithms then iterate the process of progressively altering the protein structure to have the greatest decrease in potential energy. They terminate the search after reaching a structure for which no changes to the structure further reduce this energy.

Yet returning to the chemotaxis analogy, imagine what happens if we were to place many small sugar cubes and one large sugar cube into the bacterium’s environment. The bacterium will sense the gradient not of the large sugar cube but of its nearest attractant. Because the smaller food sources outnumber the larger food source, the bacterium will likely not reach the point of greatest attractant concentration. In bacterial exploration, this is a feature, not a bug; if the bacterium exhausts one food source, then it will just move to another. But in protein structure prediction, we should be wary of a local search algorithm returning a protein structure that does not have minimum free energy but that does have the property that no “nearby” structures have lower energy.

In general, an object in a search space that has a smaller value of the optimization function than neighboring points is called a local minimum. Returning to our landscape analogy, our search space may have many valleys, but in an optimization problem, we are seeking the lowest valley over the entire landscape, called a global minimum.

STOP: How could we improve our local search algorithm for structure prediction to avoid winding up in a local minimum?

Researchers applying local search algorithms have devised a number of ways to avoid local minima, two of which are so fundamental that we should mention them. First, because the algorithm’s choice of initial conformation has a huge influence on the final conformation, we should run the algorithm multiple times with different starting conformations. This is analogous to allowing multiple bacteria to explore their environment at different starting points. Second, every time we reach a local minimum, we could allow ourselves to change the structure with some probability, thus giving our local search algorithm the chance to “bounce” out of a local minimum. Once again, randomized algorithms help us solve problems!

Applying an ab initio algorithm to a protein sequence

To run an ab initio structure prediction algorithm on a real protein, we will use a software resource called QUARK, which is built upon the ideas discussed in the previous section, with some added features. For example, QUARK’s algorithm applies a combination of multiple scoring functions to look for the lowest energy conformation across all of these functions.

Levinthal’s paradox means that the search space of all possible structures for a protein is so large that accurately predicting large protein structures with ab initio modeling remains very difficult. As such, QUARK limits us to proteins with at most 200 amino acids, and so we will run it only on human hemoglobin subunit alpha.

Toward a faster approach for protein structure prediction

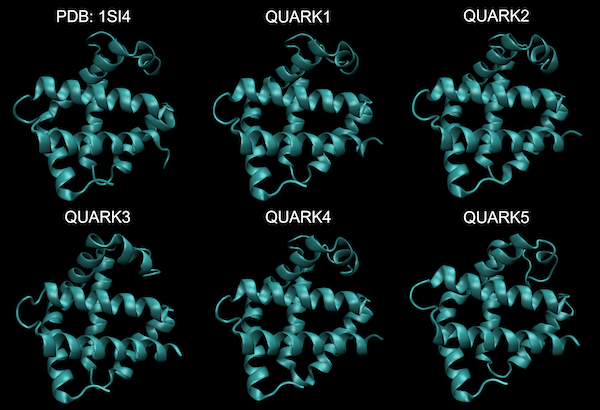

The figure below shows the top five predicted human hemoglobin subunit alpha structures returned by QUARK as well as the protein’s experimentally verified structure, and an average of these six structures. It takes a keen eye to see any differences between these structures. We conclude that ab initio prediction can be accurate.

The experimentally verified protein structure of human hemoglobin subunit alpha (top left) along with five models of this protein produced by QUARK from the protein’s primary sequence, all of which are nearly indistinguishable from the verified structure with the naked eye.

The experimentally verified protein structure of human hemoglobin subunit alpha (top left) along with five models of this protein produced by QUARK from the protein’s primary sequence, all of which are nearly indistinguishable from the verified structure with the naked eye.

Yet we also wonder if we can speed up our structure prediction algorithms so that they will scale to a larger protein like the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. In the next lesson, we will learn about another type of protein structure prediction that uses a database of known structures.

Leanpub

Leanpub