Protein structure prediction is an old problem. In 1967, the Soviets founded an entire research insitute dedicated to solving “the protein problem”; this institute still lives on today. Despite the difficulty of protein structure prediction, gradual algorithmic improvements and increasing computational resources have led biologists around the world to wish for the day when they could consider protein structure prediction to be solved.

That day has come. Kind of.

Every two years since 1994, a global contest called Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) has allowed modelers to test their protein structure prediction algorithms against each other. The contest organizers compile a secret collection of experimentally verified protein structures and then run all submitted algorithms against these proteins.

In 2020, the 14th iteration of this contest (CASP14) was won in a landslide. The second version of AlphaFold,1 a DeepMind project, vastly outperformed the world’s foremost structure prediction approaches.

The algorithm powering AlphaFold is an extremely involved method based on deep learning, a topic that we will discuss in this work’s final module. If you’re interested in learning more about this algorithm, consult the AlphaFold website or this excellent blog post by Mohammed al Quraishi: https://bit.ly/39Mnym3.

Instead of using RMSD, CASP scores a predicted structure against a known structure using the global distance test (GDT). This test first asks, “How many corresponding alpha carbons are close to each other in the two structures?” To answer this question, we take the percentage of corresponding alpha carbon positions whose distance from each other is at most equal to some threshold t. The GDT score averages the percentages obtained when t is equal to each of 1, 2, 4, and 8 angstroms. A GDT score of 90% is considered good, and a GDT score of 95% is considered excellent (i.e., comparable to minor errors resulting from experimentation) 2.

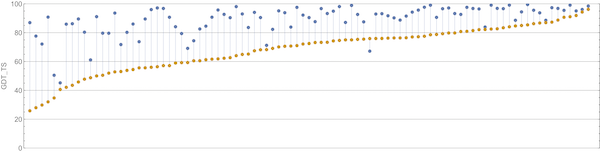

We will show a few plots to illustrate the decisiveness of AlphaFold’s CASP victory. The first graph, which is shown in the figure below, compares the GDT scores of AlphaFold against the second-place algorithm (a product of David Baker’s laboratory, which developed the Robetta and Rosetta@Home software).

A plot of GDT scores for the AlphaFold2 (blue) and Baker lab (orange) submissions over all proteins in the CASP14 contest. AlphaFold2 finished first in CASP14, and Baker lab finished second. Image courtesy: Mohammed al Quraishi.

A plot of GDT scores for the AlphaFold2 (blue) and Baker lab (orange) submissions over all proteins in the CASP14 contest. AlphaFold2 finished first in CASP14, and Baker lab finished second. Image courtesy: Mohammed al Quraishi.

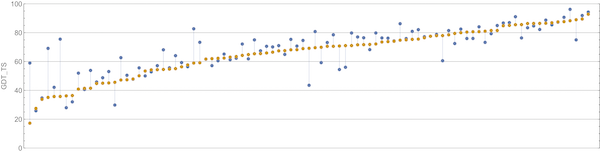

We can appreciate the size of the margin of victory in the above figure if we compare it against the difference between the second and third place competitors, shown in the figure below.

A plot of GDT scores for the Baker lab (blue) and Zhang lab (orange) submissions for all proteins in the CASP14 contest. Baker lab finished second in CASP14, and Zhang lab finished third. Image courtesy: Mohammed al Quraishi.

A plot of GDT scores for the Baker lab (blue) and Zhang lab (orange) submissions for all proteins in the CASP14 contest. Baker lab finished second in CASP14, and Zhang lab finished third. Image courtesy: Mohammed al Quraishi.

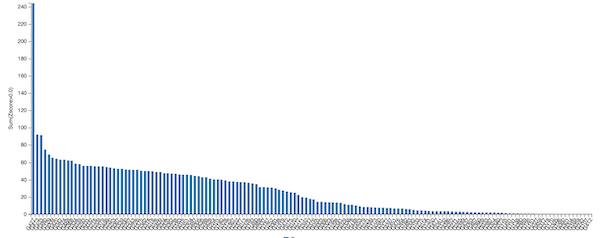

For each protein in the CASP14 contest, we can also compute each algorithm’s z-score, defined as the number of standard deviations that the algorithm’s GDT score falls from the mean GDT score over all competitors. For example, a z-score of 1.4 would imply that the approach performed 1.4 standard deviations above the mean, and a z-score of -0.9 would imply that the approach performed 0.9 standard deviations below the mean.

Summing all of an algorithm’s positive z-scores gives a reasonable metric for the relative quality of an algorithm compared to its competitors. If this sum of z-scores is large, then the algorithm performed significantly above average on the prediction of some proteins. The figure below shows the sum of z-scores for all CASP14 participants and reiterates the margin of AlphaFold’s victory, since its sum of z-scores is twice that of the second place algorithm.

A bar chart plotting the sum of z-scores for every entrant in the CASP14 contest. AlphaFold2 is shown on the far left; its sum of z-scores is over double that of the second-place submission. Source: https://predictioncenter.org/casp14/zscores_final.cgi.

A bar chart plotting the sum of z-scores for every entrant in the CASP14 contest. AlphaFold2 is shown on the far left; its sum of z-scores is over double that of the second-place submission. Source: https://predictioncenter.org/casp14/zscores_final.cgi.

AlphaFold’s CASP14 triumph led some scientists — and media outlets — to declare that protein structure prediction had finally been solved3. Yet some critics remained skeptical.

Although AlphaFold obtained an impressive median RMSD of 1.6 angstroms for its predicted proteins, about a third of these predictions have an RMSD over 2.0 angstroms, which we mentioned earlier is often used as a threshold for whether a predicted structure is reliable. For a given protein, we will not know in advance whether AlphaFold’s predicted structure is outside of this range unless we experimentally validate the protein’s structure.

Furthermore, some experts have claimed that to be completely trustworthy for a sensitive application like designing drugs to target proteins implicated in diseases, the RMSD of predicted protein structures would need to be nearly an order of magnitude lower, i.e., closer to 0.2 angstroms.

Finally, the AlphaFold algorithm is “trained” using a database of known protein structures, which makes it more likely to succeed if a protein is similar to a known structure. But the proteins with structures that are dissimilar to any known structure are the ones possessing some of the greatest scientific interest.

Pronouncing protein structure prediction to be solved may be hasty, but we will likely never again see such a clear improvement to the state of the art for structure prediction. AlphaFold represents, perhaps, the final great innovation for a research problem that has puzzled biologists for over half a century.

Thus ends our discussion of protein structure prediction, but we still have much more to say. In particular, when comparing two protein structures, we have relied only upon the RMSD between the vectorizations of these two structures after applying the Kabsch algorithm. But using a single statistic to represent the differences between two protein structures masks what those differences might be. Furthermore, proteins are not static objects; they bend and shape in the cell as they perform their tasks. We will therefore now transition to a second part of our discussion of protein analysis, in which we show additional methods used to compare proteins and apply these techniques to the validated structures of the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins.

Continue to part 2: spike protein comparison

-

Jumper, J et al. 2021. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596: 583–58. Available online ↩

-

AlQuraishi, M. 2020, December 8. AlphaFold2 @ CASP14: “It feels like one’s child has left.” Retrieved January 20, 2021, from https://bit.ly/39Mnym3 ↩

-

Service, R. F. (2020, November 30). ‘The game has changed.’ AI triumphs at solving protein structures. Science. doi:10.1126/science.abf9367 ↩