The central dogma of molecular biology

DNA is a double-stranded molecule consisting of the four nucleobases adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine; the sum total of a cell’s DNA constitutes its genome. A gene is a region of an organism’s DNA that is transcribed into a single-stranded RNA molecule in which thymine is converted to uracil and the other bases remain the same.

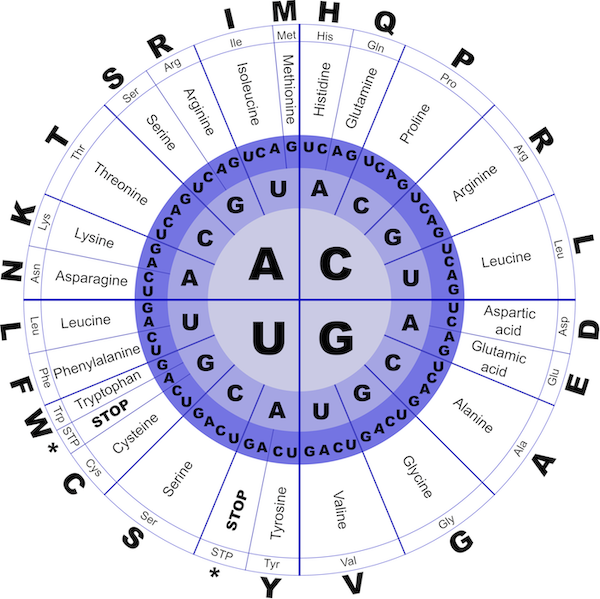

The RNA transcript is then translated into the amino acid sequence of a protein. Because there are four different nucleobases but twenty amino acids, RNA is translated in codons, or triplets of nucleobases, according to a mapping called the genetic code (see figure below).

The genetic code, which dictates the conversion of RNA codons into amino acids. Codons are read from the inside of the figure outward. Image courtesy J_Alves, Open Clip Art.

The genetic code, which dictates the conversion of RNA codons into amino acids. Codons are read from the inside of the figure outward. Image courtesy J_Alves, Open Clip Art.

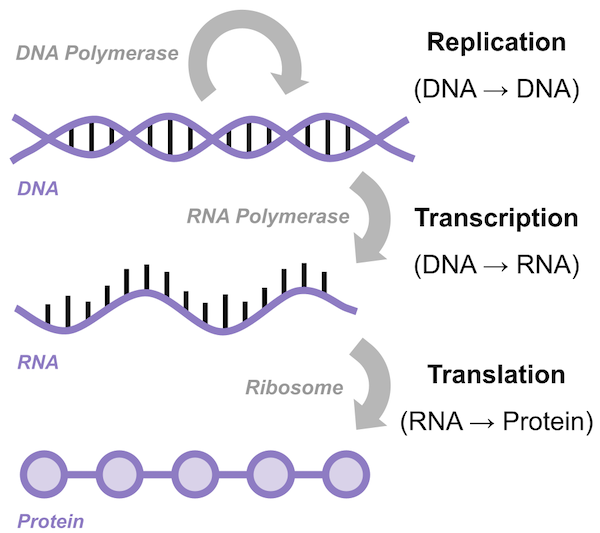

DNA can therefore be thought of as a blueprint for storing information that flows from DNA to RNA to protein. This flow of information is called the central dogma of molecular biology, illustrated in the figure below.

Note: Like any dogma, there are times in which the central dogma of molecular biology is violated. If you are interested in an example, consider Chapter 4 of Bioinformatics Algorithms.

The central dogma of molecular biology states that genetic information flows from DNA in the nucleus, into the RNA that is transcribed from DNA, and then into proteins that are translated from RNA and that then serve some purpose in the cell.

The central dogma of molecular biology states that genetic information flows from DNA in the nucleus, into the RNA that is transcribed from DNA, and then into proteins that are translated from RNA and that then serve some purpose in the cell.

Transcription factors control gene regulation

All your cells have essentially the same DNA, and yet your liver cells, heart cells, and brain cells serve different functions. This is because the rates at which your genes are regulated, or converted into RNA and then protein, vary for different cell types and in response to different stimuli.

Gene regulation typically occurs at either the DNA or protein level. At the DNA level, regulation is modulated by transcription factors, master regulator proteins that typically bind to the DNA immediately preceding a gene and serve to either activate or repress the gene’s rate of transcription, turning that rate up or down, respectively.

Because of the central dogma, transcription factors are involved in a feedback loop. DNA is transcribed into RNA, which is translated into the protein sequence of a transcription factor, which then binds to the upstream region of a gene and changes its rate of transcription.

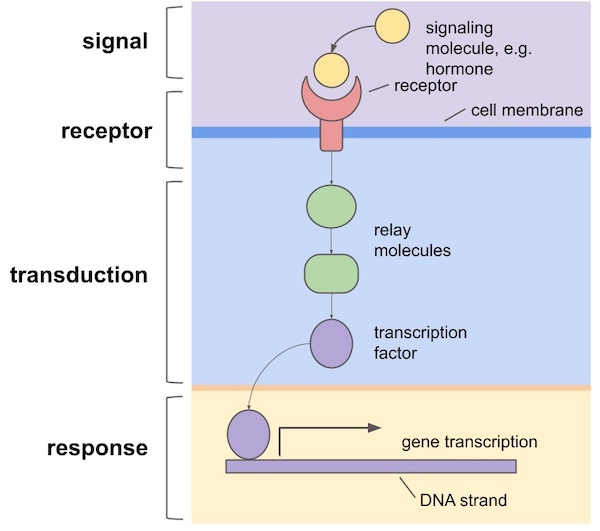

Transcription factors are vital for the cell’s response to its environment because extracellular stimuli can activate a transcription factor via a system of signaling molecules that convey a signal through relay molecules to the transcription factor (see figure below). Only when the transcription factor is activated will it regulate its target gene(s).

A cell receiving a signal which triggers a response in which this signal is “transduced” into the cell, resulting in transcription of a gene. We will discuss signal transduction in greater detail in a future module.1

A cell receiving a signal which triggers a response in which this signal is “transduced” into the cell, resulting in transcription of a gene. We will discuss signal transduction in greater detail in a future module.1

In module 2, we will discuss the details of how the cell detects an extracellular signal and conveys it as a response within the cell. For now, we will focus on the relationship between transcription factors and the genes that they regulate.

Determining if a transcription factor regulates a given gene

A transcription factor has a weak binding affinity to DNA in general, but it has a very strong binding affinity for a single specific short sequence of nucleotides2 called a sequence motif. Think of a transcription factor as latching onto DNA and then sliding up and down the DNA molecule until it finds its target motif, where it clamps down. If this motif occurs immediately before a gene, then the transcription factor will regulate this gene.

Note: The astute reader will notice that we have already used the term “motif” in two different contexts, first to mean both a recurring network substructure and now to mean a sequence of nucleotides to which a transcription factor binds. This sequence is called a “motif” because the transcription factor may regulate multiple genes, so that the binding sequence will occur immediately before most or all of these genes.

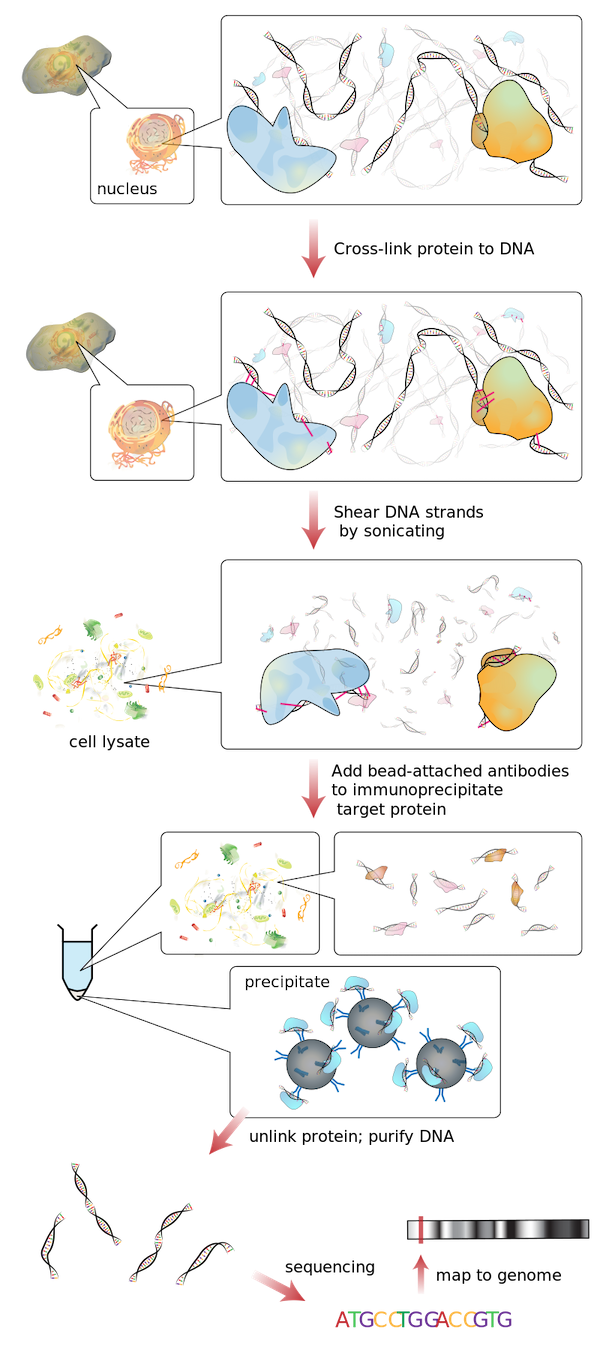

A natural question, then, is to find the set of genes to which a transcription factor binds. A common experiment answering this question is called ChIP-seq3, which is short for chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing. This approach, which is illustrated in the figure below, combines an organism’s DNA with multiple copies of a protein of interest that binds to DNA (which in this case would be a transcription factor). After allowing for the proteins to bind naturally to the DNA, the DNA is cleaved into much smaller fragments of a few hundred base pairs. As a result, we obtain a collection of DNA fragments, some of which are attached to a copy of our protein of interest.

The question is how to isolate the fragments of DNA that are bound to a transcription factor of interest, and the clever trick is to use an antibody. Normally, antibodies are produced by the immune system to target foreign pathogens. The antibody used by ChIP-seq is designed to bind to our protein of interest, and the antibody is attached to a bead. Once the antibody attaches to the protein target, a complex is formed consisting of the DNA fragment, the protein bound to the DNA, the antibody bound to the protein, and the bead attached to the antibody. Because the bead weighs down these complexes, they can be filtered out as preciptate from the solution, and we are left with just the DNA fragments that are bound to our protein.

In a final step, the protein is unlinked from the DNA, leaving a collection of DNA fragments that were previously bound to a single protein. Each fragment is read using DNA sequencing to determine its order of nucleotides, which is then queried against the genome to determine the gene(s) that the fragment precedes. When the protein is a transcription factor, we can therefore hypothesize that these are the genes that the transcription factor regulates!

An overview of ChIP-seq. Figure courtesy Jkwchui, Wikimedia Commons user.

An overview of ChIP-seq. Figure courtesy Jkwchui, Wikimedia Commons user.

If you would like a different explanation of may also like to check out the following excellent video on identifying genes regulated by a transcription factor. This video was produced by students in the 2020 PreCollege Program in Computational Biology at Carnegie Mellon. The presenters won an award from their peers for their work, and for good reason!

STOP: How do you think that researchers could determine whether a transcription factor activates or represses a given gene?

As a result of techniques like ChIP-seq, researchers have learned a great deal about which transcription factors regulate which genes. The key is to organize the relationships between transcription factors and the genes that they regulate in a way that will help us identify patterns in these relationships.

-

CC https://www.open.edu/openlearn/science-maths-technology/general-principles-cellular-communication/content-section-1 ↩

-

Goodsell, David (2009), The Machinery of Life. Copernicus Books. ↩

-

Johnson, D. S., Mortazavi, A., Myers, R. M., & Wold, B. (2007). Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA interactions. Science, 316(5830), 1497–1502. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1141319 ↩

Leanpub

Leanpub