Biological oscillators must be robust

If your heart skips a beat when you are watching a horror movie, then it should return quickly to its natural rhythm. When you hold your breath to dive underwater, your normal breathing resumes at the surface. And regardless of what functions your cells perform, they should be able to maintain a normal cell cycle despite disturbance.

An excellent illustration of oscillator robustness is the body’s ability to handle jet lag. There is no apparent reason why we would have evolved to fly halfway around the world in a few hours. And yet our circadian clock is so resilient that after a few days of fatigue and crankiness, it returns us to a normal daily cycle.

In the previous lesson, we saw that the repressilator, a three-element motif, can exhibit oscillations even in a noisy environment of randomly moving particles. The repressilator’s resilience makes us wonder how well it can respond to a disturbance in the concentrations of its particles.

A coarse-grained repressilator model

With our work on Turing patterns in the prologue, tracking the movements of many individual particles led to a slow simulation that did not scale well given more particles or reactions. This observation led us to devise a coarse-grained reaction-diffusion model that was still able to produce Turing patterns. We used a cellular automaton because the concentrations of particles varied in different locations and were diffusing at different rates.

We would like to devise a coarse-grained model of the repressilator. However, the particles diffuse at the same rate and are uniform across the simulation, and so there is no need to track concentrations in individual locations. As a result, we will use a simulation that assumes that particles are well-mixed.

For example, say that we are modeling a degradation reaction. If we start with a concentration of 10,000 X particles, then after a single time step, we will simply multiply the number of X particles by (1-k), where k is a parameter related to the rate of the degradation reaction.

As for a repression reaction like X + Y → X, we can update the concentration of Y particles by subtracting some factor r times the current concentrations of X and Y particles.

We will further discuss the technical details required to implement a well-mixed reaction-diffusion model in the next module. In the meantime, we would like to see what happens when we make a major disturbance to the concentration of one of the particles in the well-mixed model. Do particle concentrations resume their oscillations? To build this model of the repressilator, check out the following tutorial.

The repressilator is robust to disturbance

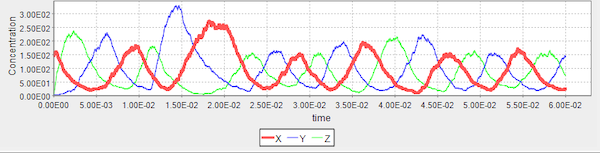

The figure below shows plots over time of particle concentrations in our well-mixed simulation of the repressilator. (Note that these plots are less noisy than the ones that we produced previously because we are assuming a well-mixed environment.) Midway through this simulation, we greatly increase the concentration of Y particles.

A plot of particle concentrations in the well-mixed repressilator model over time. Adding a significant number of Y particles to our simulation (the second blue peak) produces little ultimate disturbance to the concentrations of the three particles, which return to normal oscillations within a single cycle.

A plot of particle concentrations in the well-mixed repressilator model over time. Adding a significant number of Y particles to our simulation (the second blue peak) produces little ultimate disturbance to the concentrations of the three particles, which return to normal oscillations within a single cycle.

Because of the spike in the concentration of Y, the reaction Y + Z → Y suppresses the concentration of Z for longer than usual, and so the concentration of X is free to increase for longer than normal. As a result, the next peak of X particles is higher than normal.

We might hypothesize that this process would continue, with a tall peak in the concentration of Z. However, the peak in the concentration of Z is no taller than normal, and the following peak shows a normal concentration of Y. The system has very quickly absorbed the blow of an increase in concentration of Y and returned to normal within one cycle.

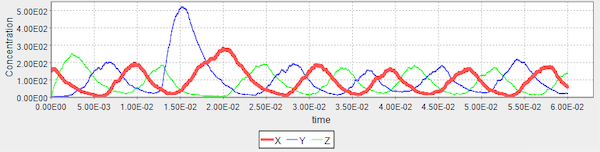

Even with a much larger jolt to the concentration of Y, the concentrations of the three particles return to normal oscillations very quickly, as shown below.

A larger increase in the concentration of Y particles than in the previous figure does not produce a substantive change in the system.

A larger increase in the concentration of Y particles than in the previous figure does not produce a substantive change in the system.

The repressilator is not the only network motif that leads to oscillations of particle concentrations, but robustness to disturbance is a shared feature of all these motifs. Furthermore, the repressilator is not the most robust oscillator that we can build. Researchers have shown that at least five components are typically needed to build a very robust oscillator,1 which may help explain why real oscillators tend to have more than three components.

In the next module, we will encounter a much more involved biochemical process, with far more molecules and reactions, that is used by bacteria to cleverly (and robustly) explore their environment. In fact, we will have so many particles and so many reactions that we will need to completely rethink how we formulate our model.

In the meantime, check out the exercises below to continue building your understanding of transcription factor networks and network motifs.

-

Castillo-Hair, S. M., Villota, E. R., & Coronado, A. M. (2015). Design principles for robust oscillatory behavior. Systems and Synthetic Biology, 9(3), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11693-015-9178-6 ↩