Cells detect and transduce signals via receptor proteins

Chemotaxis is one of many ways in which a cell must perceive a change in its environment and react accordingly. This response is governed by a process called signal transduction, in which a cell identifies a stimulus outside the cell and then transmits this stimulus into the cell.

When a certain molecule’s extracellular concentration increases, receptor proteins on the outside of the cell have more frequent binding with these molecules and are therefore able to detect changes in molecular concentration. This signal is then “transduced” via a series of internal chemical processes.

For example, transcription factors, which we discussed in the previous module, are involved in a signal transduction process. When some extracellular molecule is detected, a cascade begins that eventually changes a transcription factor into an active state, so that it is ready to activate or repress the genes that it regulates.

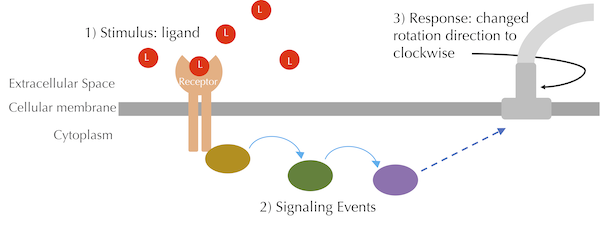

In the case of chemotaxis, E. coli has receptor proteins that detect attractants such as glucose by binding to and forming a complex with these attractant ligands. The bacterium also contains receptors to detect repellents, but we will focus on modeling the binding of a single type of receptor to a single type of attractant ligand. In later lessons, we will enter the cell and model the cascade of reactions after this binding has occurred, as shown in the figure below, which cause a change in the rotation of one or more flagella.

A high-level overview of the chemotaxis signaling pathway. The red circles labeled L represent attractant ligands. When these ligands bind to receptors, a signal is transduced inside the cell via a series of enzymes, which eventually influences the rotation direction of a flagellum.

A high-level overview of the chemotaxis signaling pathway. The red circles labeled L represent attractant ligands. When these ligands bind to receptors, a signal is transduced inside the cell via a series of enzymes, which eventually influences the rotation direction of a flagellum.

In this lesson, we will discuss how to model ligand-receptor binding.

Ligand-receptor dynamics can be modeled by a reversible reaction

The chemical reactions that we have considered earlier in this course are irreversible, meaning they can only proceed in one direction. For example, in the prologue’s reaction-diffusion model, we modeled the reaction A + 2B → 3B, but we did not consider the reverse reaction 3B → A + 2B.

To model ligand-receptor dynamics, we will use a reversible reaction that proceeds continuously in both directions at possibly different rates. If a ligand collides with a receptor, then there is some probability that the two molecules will bind into a complex. At the same time, in any unit of time, there is also some probability that a bound receptor-ligand complex will dissociate into two separate molecules. The better suited a receptor is to a ligand, the higher the binding rate and the lower the dissociation rate. In a future module, we will discuss some of the biochemical details underlying what makes two molecules more or less likely to bind and disssociate.

Note: You may be wondering why ligand-receptor binding is reversible. If complexes did not dissociate, then a brief increase in ligand concentration would be detected indefinitely by the surface receptors. Without releasing the bound ligands, the cell would need to manufacture more receptors, which are complicated molecules.

We denote the ligand molecule by L, the receptor molecule by T, and the bound complex by LT. The reversible reaction representing complex binding and dissociation is L + T ←→ LT and consists of two reactions. The forward reaction is L + T → LT, which occurs at a rate depending on some rate constant kbind, and the reverse reaction is LT → L + T, which occurs at a rate depending on some rate constant kdissociate.

If we start with a free floating supply of L and T molecules, then LT complexes will initially be formed quickly at the expense of the free-floating L and T molecules. The reverse reaction will not occur because of the lack of LT complexes. However, as the concentration of LT grows and the concentrations of L and T decrease, the rate of increase in the concentration of LT will slow. Eventually, the number of LT complexes being formed by the forward reaction will balance the number of LT complexes being split apart by the reverse reaction. At this point, the concentration of all particles reaches equilibrium.

Calculation of equilibrium in a reversible ligand-receptor reaction

For a single reversible reaction, if we know the rates of both the forward and reverse reactions, then we can calculate the steady state concentrations of L, T, and LT by hand. Suppose that we begin with initial concentrations of L and T that are represented by l0 and t0, respectively. Let [L], [T], and [LT] denote the concentrations of the three molecule types. And assume that the reaction rate constants kbind and kdissociate are fixed.

When the steady state concentration of LT is reached, the rates of the forward and reverse reactions are equal. In other words, the number of complexes being produced is equal to the number of complexes dissociating:

kbind · [L] · [T] = kdissociate · [LT].

We also know that by the law of conservation of mass, the concentrations of L and T are always constant across the system and are equal to their initial concentrations. That is, at any time point,

[L] + [LT] = l0

[T] + [LT] = t0.

We solve these two equations for [L] and [T] to yield

[L] = l0 - [LT]

[T] = t0 - [LT].

We substitute the expressions on the right for [L] and [T] into our original steady state equation:

kbind · (l0 - [LT]) · (t0 - [LT]) = kdissociate · [LT]

We then expand of the left side of the above equation:

kbind · [LT]2 - (kbind · l0 + kbind · t0) · [LT] = kdissociate · [LT] + kbind · l0 · t0

Finally, we subtract the right side of this equation from both sides:

kbind · [LT]2 - (kbind · l0 + kbind · t0 + kdissociate) · [LT] + kbind · l0 · t0 = 0

This equation may look daunting, but most of its components are constants. In fact, the only unknown is [LT], which makes this a quadratic equation, with [LT] as the variable.

In general, a quadratic equation has the form a · x2 + b · x + c = 0 for a single variable x and constants a, b, and c. In our case, x = [LT], a = kbind, b = - (kbind · l0 + kbind · t0 + kdissociate), and c = kbind · l0 · t0. The quadratic formula — which you may have thought you would never use again — tells us that the quadratic equation has solutions for x given by

\[x = \dfrac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4 \cdot a \cdot c}}{2 \cdot a}\,.\]STOP: Use the quadratic formula to solve for [LT] in our previous equation and find the steady state concentration of LT. How can we use this solution to find the steady state concentrations of L and T as well?

Now that we have reduced the computation of the steady state concentration of LT to the solution of a quadratic equation, we will compute this steady state concentration for a sample collection of parameters. Say that we are given the following parameter values (the units of these parameters are not important for this toy example):

- kbind = 2;

- kdissociate = 5;

- l0 = 50;

- t0 = 50.

Substituting these values into the quadratic equation, we obtain the following:

- a = kbind = 2

- b = - (kbind · l0 + kbind · t0 + kdissociate) = -205

- c = kbind · l0 · t0 = 5000

That is, we are solving the equation 2 · [LT]2 - 205 · [LT] + 5000 = 0. Using the quadratic formula to solve for [LT] gives

\([LT] = \dfrac{205 \pm \sqrt{205^2 - 4 \cdot 2 \cdot 5000}}{2 \cdot 2} = 51.25 \pm 11.25\).

It would seem that this equation has two solutions: [LT] = 51.25 + 11.25 = 62.5 and [LT] = 51.25 - 11.25 = 40. Yet because l0 and t0, the respective initial concentrations of L and T, are both equal to 50, the first “solution” would imply that [L] = l0 - [LT] = 50 - 62.5 = -12.5 and [T] = t0 - [LT] = 50 - 62.5 = -12.5, which is impossible because the concentration of a particle cannot be negative.

Now that we know the steady state concentration of LT must be 40, we can recover the values of [L] and [T] as

[L] = l0 - [LT] = 10

[T] = t0 - [LT] = 10.

What if the forward reaction were slower (i.e., kbind were lower)? We would imagine that the equilibrium concentration of LT should decrease. For example, if we halve kbind, then we obtain the following adjusted parameter values:

-

a = kbind = 1

-

b = - (kbind · l0 + kbind · t0 + kdissociate) = -105

-

c = kbind · l0 · t0 = 2500

In this case, if we solve the quadratic equation for [LT], then we obtain

\([LT] = \dfrac{105 \pm \sqrt{105^2 - 4 \cdot 1 \cdot 2500}}{2 \cdot 1} = 52.5 \pm 16.008\).

The only feasible solution is 52.5-16.008 = 36.492; As anticipated, the steady state concentration has decreased.

STOP: What do you think will happen to the steady state concentration of LT if its initial concentration (l0) increases or decreases? What if the dissociation rate (kdissociate) increases or decreases? Confirm your predictions by changing these parameters and applying the quadratic formula to find the concentration of [LT].

Where are the units?

We have conspicuously not provided any units in the calculations above for the sake of simplicity, and so we will pause to explain what these units are. The concentration of a particle (whether it is L, T, or LT) is measured in molecules/µm3, the number of molecules per unit volume. But what about the binding and dissociation rates?

When we multiply the binding rate constant kbind by the concentrations [L] and [T], the resulting unit should be in molecules/µm3 per second, which corresponds to the rate at which the concentration [LT] of complexes is increasing. If we let y denote the unknown units of kbind, then

y · (molecules/µm3) · (molecules/µm3) = (molecules/µm3)s-1

and solving for y gives

y = ((molecules/µm3)-1)s-1.

STOP: Use a similar argument to show that the units of the dissociation rate kdissociate should be s-1.

Steady state ligand-receptor concentrations for an experimentally verified example

Having established the units in our model, we will solve our quadratic equation once more to identify steady state concentrations using experimentally verified binding and dissociation rates. The experimentally verified rate constant for the binding of receptors to glucose ligands is kbind = 0.0146 ((molecules/µm3)-1)s-1, and the dissociation rate constant is kdissociate = 35s-1.123 We will model an E. coli cell with 7,000 receptor molecules in an environment containing 10,000 ligand molecules. Using these values, we obtain the following constants a, b, and c in the quadratic equation:

- a = kbind = 0.0146

- b = - (kbind · l0 + kbind · t0 + kdissociate) = -283.2

- c = kbind · l0 · t0 = 1022000

When we solve for [LT] using the quadratic formula, we obtain [LT] = 4,793 molecules/µm3. Now that we have this value along with l0 and t0, we can solve for [L] and [T] as well:

[L] = l0 - [LT] = 5,207 molecules/µm3

[T] = t0 - [LT] = 2,207 molecules/µm3

We can therefore determine the steady state concentration for a single reversible reaction. However, if we want to model real cellular processes, we will have many reactions for a variety of different particles. It will quickly become infeasible to solve all the resulting equations exactly. Instead, we need a method of simulating many reactions in parallel without incurring the significant computational overhead required to track the movements of every particle.

-

Li M, Hazelbauer GL. 2004. Cellular stoichimetry of the components of the chemotaxis signaling complex. Journal of Bacteriology. Available online ↩

-

Spiro PA, Parkinson JS, and Othmer H. 1997. A model of excitation and adaptation in bacterial chemotaxis. Biochemistry 94:7263-7268. Available online. ↩

-

Stock J, Lukat GS. 1991. Intracellular signal transduction networks. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biophysical Chemistry. Available online ↩

Leanpub

Leanpub