Transducing an extracellular signal to a cell’s interior

We now turn to the question of how the cell conveys the extracellular signal it has detected via the process of signal transduction to the cell’s interior. In other words, when E. coli senses an increase in the concentration of glucose, meaning that more ligand-receptor binding is taking place at the receptor that recognizes glucose, how does the bacterium change its behavior?

The engine of signal transduction is phosphorylation, a chemical reaction that attaches a phosphoryl group (PO3-) to an organic molecule. Phosphoryl modifications serve as an information exchange of sorts because, as we will see, they activate or deactivate certain enzymes.

A phosphoryl group usually comes from one of two sources. First, the phosphoryl can be broken off from an adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecule, the “energy currency” of the cell, producing adenosine diphosphate (ADP). Second, the phosphoryl can be exchanged from a phosphorylated molecule that loses its phosphoryl group in a dephosphorylation reaction.

For many cellular responses, including bacterial chemotaxis, a sequence of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events called a phosphorylation cascade serves to transmit information within the cell about the amount of ligand binding being detected on the cell’s exterior. In this lesson, we discuss how this cascade of chemical reactions leads to a change in bacterial movement.

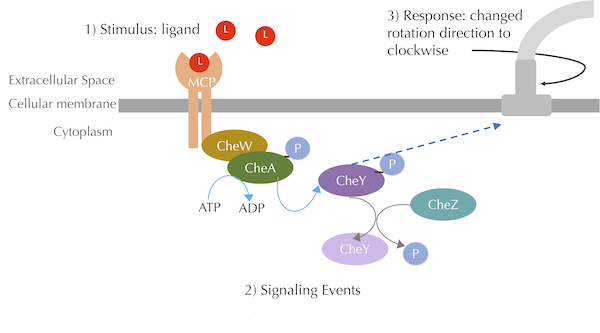

A high-level view of the transduction pathway for chemotaxis is shown in the figure below. The cell membrane receptors that we have been working with are called methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs), and they bridge the cellular membrane, binding both to ligand stimuli in the cell exterior and to other proteins on the inside of the cell. The pathway also includes a number of additional proteins, which all start with the prefix “Che” (short for “chemotaxis”).

A summary of the chemotaxis transduction pathway. A ligand binding signal is propagated through CheA and CheY phosphorylation, which leads to a response of clockwise flagellar rotation. The blue curved arrow denotes phosphorylation, the grey curved arrow denotes dephosphorylation, and the blue dashed arrow denotes a chemical interaction. Our figure is a simplified view of Parkinson Lab illustrations.

A summary of the chemotaxis transduction pathway. A ligand binding signal is propagated through CheA and CheY phosphorylation, which leads to a response of clockwise flagellar rotation. The blue curved arrow denotes phosphorylation, the grey curved arrow denotes dephosphorylation, and the blue dashed arrow denotes a chemical interaction. Our figure is a simplified view of Parkinson Lab illustrations.

On the interior of the cellular membrane, MCPs form complexes with two proteins called CheW and CheA. In the absence of MCP-ligand binding, this complex is more stable, and the CheA molecule autophosphorylates, meaning that it adds a phosphoryl group taken from ATP to itself — a concept that might seem mystical if you had not already followed our discussion of autoregulation in the previous module.

A phosphorylated CheA protein can pass on its phosphoryl group to a molecule called CheY, which interacts with the flagellum in the following way. Each flagellum has a protein complex called the flagellar motor switch that is responsible for controlling the direction of flagellar rotation. The interaction of this protein complex with phosphorylated CheY induces a change of flagellar rotation from counter-clockwise to clockwise. As we discussed earlier in the module, this change in flagellar rotation causes the bacterium to tumble, which in the absence of an increase in attractant occurs every 1 to 1.5 seconds.

Yet when a ligand binds to the MCP, the MCP undergoes conformation changes, which reduce the stability of the complex with CheW and CheA. As a result, CheA is less readily able to autophosphorylate, which means that it does not phosphorylate CheY, which cannot change the flagellar rotation to clockwise, and so the bacterium is less likely to tumble.

In summary, attractant ligand binding causes more phosphorylated CheA and CheY, which means that it causes fewer flagellar interactions and therefore less tumbling, which means that it causes the bacterium to run for a longer period of time.

Note: A critical part of this process is that if a cell with a high concentration of CheY detects an attractant ligand, then it needs to decrease its CheY concentration quickly. Otherwise, the cell will not be able to change its tumbling frequency. To this end, the cell is able to dephosphorylate CheY using an enzyme called CheZ.

Adding phosphorylation events to our model of chemotaxis

We would like to use the Gillespie algorithm that we introduced in the previous lesson to simulate the reactions driving chemotaxis signal transduction and see what happens if the bacterium “senses an attractant”, meaning that the attractant ligand’s concentration increases and leads to more receptor-ligand binding.

This model will be more complicated than any we have introduced thus far. We will need to account for both bound and unbound MCP molecules, as well as phosphorylated and unphosphorylated CheA and CheY enzymes. We will also need to model CheA phosphorylation reactions, which depend on the current concentrations of bound and unbound MCP molecules. We will at least make the simplifying assumption that the MCP receptor is permanently bound to CheA and CheW, so that we do not need to represent these molecules individually. In other words, rather than thinking about CheA autophosphorylating, we will think about the receptor that includes CheA autophosphorylating.

We will need six reactions. Two reversible reactions represent ligand-receptor binding: one for phosphorylated receptors, and another for unphosphorylated receptors. Two reactions represent MCP phosphorylation and take place at different rates based on whether the MCP is bound to a ligand (in our model, the phosphorylation rate is five times greater when the MCP is unbound). One reaction represent phosphorylation of CheY, and another reaction models dephosphorylation, which is mediated by the CheZ enzyme.

Once we have built this model, we would like to see what happens when we change the concentrations of the ligand. Ideally, the bacterium should be able to distinguish different ligand concentrations. That is, the higher the concentration of an attractant ligand, the lower the concentration of phosphorylated CheY, and the lower the tumbling frequency of the bacterium.

But does higher attractant concentration in our model really lead to a lower concentration of CheY? Let’s find out by incorporating the phosphorylation pathway into our ligand-receptor model in the following tutorial.

Changing ligand concentrations leads to a change in internal molecular concentrations

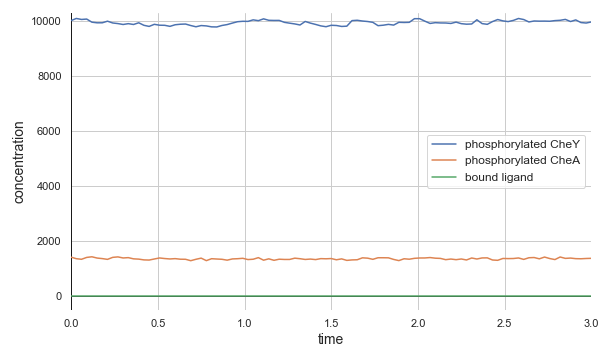

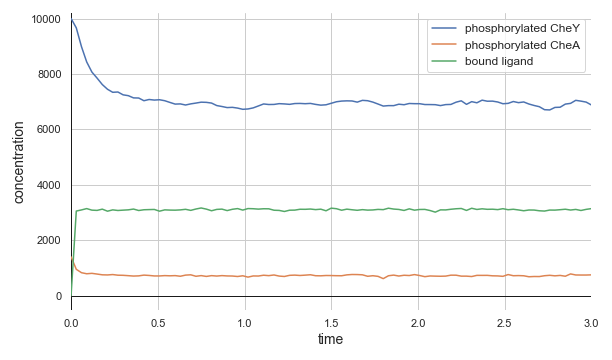

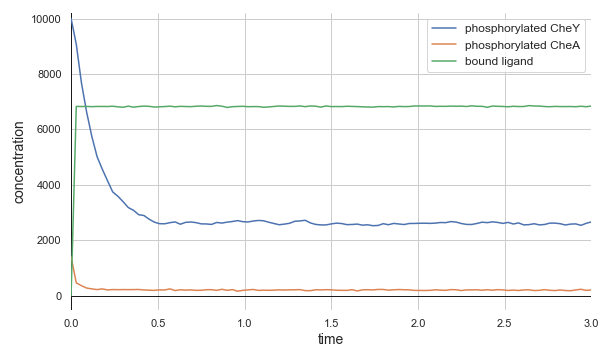

The top panel of the following figure shows the concentrations of phosphorylated CheA and CheY in a system at equilibrium in the absence of ligand. As we might expect, these concentrations remain at steady state (with some healthy noise), and so the cell stays at its background tumbling frequency. The addition of 5,000 attractant ligand molecules increases the concentration of bound receptors, therefore leading to less CheA autophosphorylation and less phosphorylated CheY (middle panel). If we instead have 100,000 initial attractant molecules, then we see an even more drastic decrease in phosphorylated CheA and CheY (bottom panel).

Molecular concentrations over time (in seconds) in a chemotaxis simulation for three different initial unbound attractant ligand concentrations: no attractant ligand (top), 5,000 ligand particles (middle), and 100,000 ligand particles (bottom). Note that the simulated cell’s bound ligand concentration (green) achieves equilibrium very quickly in each case.

Molecular concentrations over time (in seconds) in a chemotaxis simulation for three different initial unbound attractant ligand concentrations: no attractant ligand (top), 5,000 ligand particles (middle), and 100,000 ligand particles (bottom). Note that the simulated cell’s bound ligand concentration (green) achieves equilibrium very quickly in each case.

This model, powered by the Gillespie algorithm, confirms the biological observations that an increase in attractant reduces the concentration of phosphorylated CheY. The reduction takes place remarkably quickly, with the cell attaining a new equilibrium in a fraction of a second.

The biochemistry powering chemotaxis may be elegant, but it is also simple, and so perhaps it is not surprising that the model’s particle concentrations reproduced the response of E. coli to an attractant ligand.

But what we have shown in this lesson is just part of the story. In the next lesson, we will see that the biochemical realities of chemotaxis are more complicated, and for good reason — this added complexity will allow E. coli, and our model of it, to react to a dynamic world with surprising sophistication.

Leanpub

Leanpub