Introduction: Alan Turing and the Zebra’s Stripes

If you are familiar with Alan Turing, then you might be surprised that a famous computer scientist would appear in the first sentence of a book on biological modeling. After all, he is best known for two achievements that have nothing to do with biology. In 1936, Turing theorized a primitive computer consisting of a tape of cells along with a machine that writes symbols on the tape according to a set of predetermined set of rules; this “Turing machine” 1 is simple but nevertheless has been proven capable of solving any problem that a modern computer can solve. Then, during World War II, Turing worked with Allied cryptographers at Bletchley Park to devise machines that broke several German ciphers.

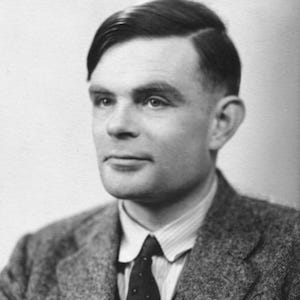

Alan Turing in 1951. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Alan Turing in 1951. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Yet in 1952, two years before his untimely demise, Turing published his only paper on biochemistry, which addressed the question: “Why do zebras have stripes?”2 He was not asking why zebras have evolved to have stripes — this question was unsolved in Turing’s time, and recent research has indicated that the stripes may be helpful in warding off flies. Rather, Turing was interested in what biochemical mechanism could produce the stripes that we see on a zebra’s coat. And he reasoned that just as a simple machine can emulate a computer, some limited set of molecular “rules” could cause stripes to appear on a zebra’s coat.

In this prologue, we will introduce a particle simulation model based on Turing’s ideas. We will be see that a system built on very simple rules and even randomness can nevertheless produce emergent behavior that is complex and elegant. And we will explore how this model can be tweaked to provide a hypothesis for the origin of not just the zebra’s stripes but also the leopard’s spots.

-

Turing, Alan M. (1936), “On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem”, Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Ser. 2, Vol. 42: 230-265. ↩

-

Turing, Alan (1952). “The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis” (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 237 (641): 37–72. Bibcode:1952RSPTB.237…37T. doi:10.1098/rstb.1952.0012. JSTOR 92463. ↩

Leanpub

Leanpub